The EU Referendum

[h5]On June, 23rd 2016 the electorate of the United Kingdom voted to end the state’s membership of the European Union: An analysis of what contributed to this outcome.[/h5]

The UK had joined the European Community in 1973 and then confirmed its membership in 1975 in a referendum with a 66 per cent majority of those who voted. Brandishing the campaign slogan ‘Vote leave, take control’, the Leave side in 2016 secured a narrow majority, 51.9 per cent of all those who voted. 13 million registered voters did not turn out at the ballot boxes. Some seven million eligible adults were not registered to vote in 2016. They were disproportionately ‘the young, flat-dwellers, especially renters; members of ethnic minorities; [and] recent movers’ (Johnston et al., 2015). Many people chose not to register to vote because they feared debt collection agencies that are allowed access to the electoral register even of those who request anonymity on the public role. Furthermore, all these figures do not include the millions of mainland EU citizens and 16 and 17 year olds who were not allowed to vote because of earlier political decisions made over who was eligible to vote and had a legitimate interest in the outcome. The outcome was unexpected by the polls, markets, politicians and almost all pundits.

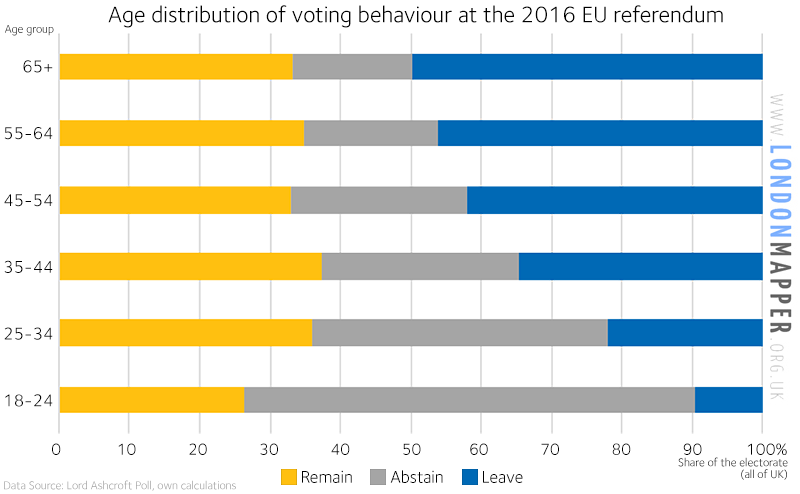

Amongst those that voted the immediate picture that emerged from the polls published after the referendum was confusing. Several polls, such as those paid for by Lord Ashcroft and used for this analysis, agreed that the older people were those who were more likely to vote for Leave, while the youngest had the largest share voting for Remain. However, when taking the total electorate into account, and considering those who chose not to vote (or spoilt their ballot), this picture became far less clear than it first seemed:

It might have been the youngest who voted overwhelmingly for Remain as a share of votes (73 per cent of those age 18 to 24), but it were also the youngest age groups who had the largest share of the electorate that decided not to vote. Among the 18 to 24 year olds 64 per cent abstained, which in turn reduces the total share of the electorate voting for Remain in that group to 26 per cent, with those who voted Leave being 10 per cent of all registered electors aged 18-24.

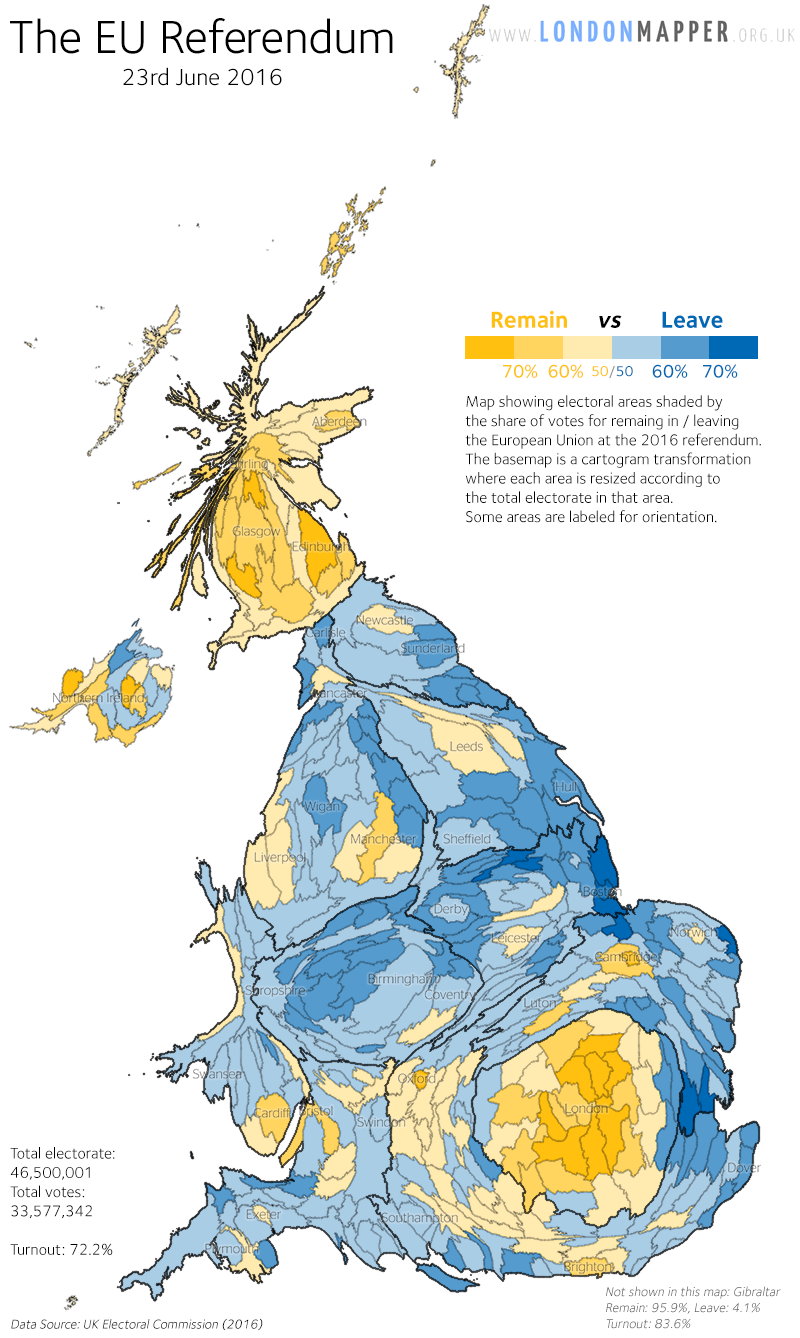

Another less considered factor of the voting patterns is that of the geographical distribution of votes across the regions and countries of the United Kingdom going beyond the overall outcome that emerges from the following cartogram where the UK areas are resized according to the total electorate there:

When comparing how the electorate is distributed across the country to how the Remain and Leave votes, as well as to how the abstentions were distributed, there are distinct geographical differences to be seen across the UK. In contrast to surprise expressed at the time over its Leave majority, Wales is actually the least unusual part of the UK, with its shares of Remain, Leave and No Vote being almost equal to the total UK shares. The South East, in contrast, has a much lower proportion of No Votes than its share of the electorate would predict if there were no geographical influences while at the same time having above average shares of Remain as well as Leave Votes. At the other extreme, disproportionate shares of the electorate chose to not vote in the strongholds of Remain, in London and Scotland. Had turnout in London and Scotland been nearer the UK average, this story would be very different:

The vote in June’s EU referendum will be a divisive element in the United Kingdom’s politics for years to come. A closer look at the voting patterns is essential to make more sense of the implications and the underlying divisions in society that need addressing and understanding if we are to know the likely future route of politics in the country. Was it complacency among life’s winners, and in those areas where it was most assumed that Remain would prevail that led to this outcome? Not so much a protest vote as a lack of voting in London, in Scotland and among the young, among those not given a vote at ages 16 and 17, and among those who had the most interest of all in the outcome: the citizens of Europe who lived in the UK but were not born in the UK and who had assumed that this would not matter in what, until 2016, was slowly becoming an ever closer union.